git is one of the most used version control systems out there. It is super versatile but this comes also with a price. It can get fairly complicated how git works. So let us have a look with some given examples.

git init or git clone

There are two ways to use git:

git initwhich creates a local empty repositorygit clonewhich clones a repository for example from GitHub

git init is no real magic. It just creates a .git folder with some meta-information about your project. When you use git clone those meta-information are already present. The most important information might be: Where is the remote repository url?

If you start with an empty repository and do your work and create some changes you would go to GitHub, create a repository there and copy&paste the URL to your freshly created repo. After that you would do this the push your stuff to GitHub: git remote add origin [copied web address].

But wait, there is a lot to unpack here.

What is remote, origin and local?

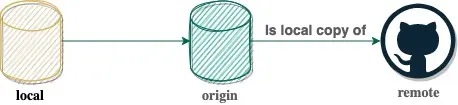

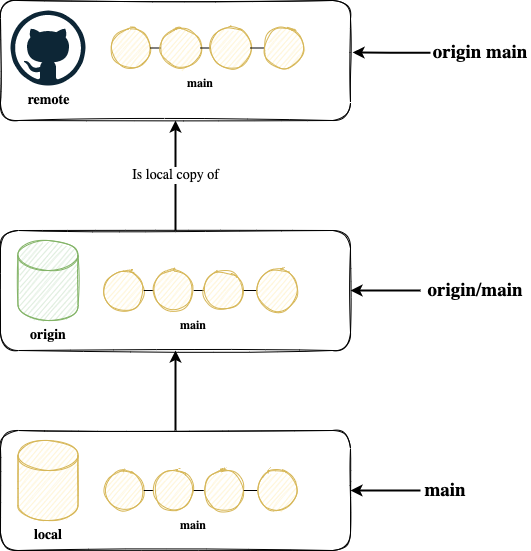

If you have a repository for example on GitHub and also work locally, you have indeed 3 versions of that repository.

- Remote: In simple terms remote is just another git repository somewhere else with the intention to keep your version and its version in sync.

- origin: Origin is your local version of the remote repository. It is not necessarily in sync nor does the remote version exist anymore. Why we have that we will see later. All information is kept inside the .git folder.

- local: Basically your current checked out version. If you add a commit, you will be ahead of origin.

We will know see example by example why we have them and how do they work.

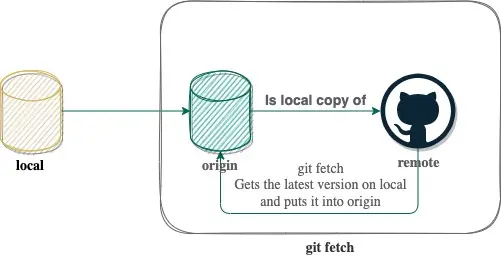

git fetch

One of the most common operations is git fetch. This command does not update your local copy.

The only thing it does it to go to the remote repository and get the latest changes and mirror them into your origin state. The idea behind almost all git commands is to be non-destructive. That is why you have a mirror of the remote repository which is not your current working set. Before I tell what happens to get changes from origin to local we have to understand how git works.

git branches and commits

A central concept of git is using branches and creating commits. Let's have a look what that is. Let's start with a commit. A commit is nothing more than the difference between the last commit and the changes you did right now plus some meta-information (the infamous hash, author, timestamp, ...). Of course that can be modified files, added files or even deleted files. It is crucial to understand that git only safes the diff (difference) between two commits. This works perfectly for a given reason:

Every commit (indicated as this yellow bubble) has a parent. As everyone has only incremental changes we can just go along the whole graph to construct the "whole" working set at any given commit.

The reason git saves only incremental changes aka diffs is, that it saves a lot of space. Just imagine you have a 100kb file where you only change a single character. Instead of storing once again 100kb, the diff is only some bytes in size. To recap: If you want to have the latest changes you just have to replay all the diffs. If you call git add you are "staging" your changes and afterwards with git commit you "transform" them into a commit. Also a commit is "immutable". That said if you create one you can just not edit them. Operations like amend or rebase will create new commits. That is important and we will see later why.

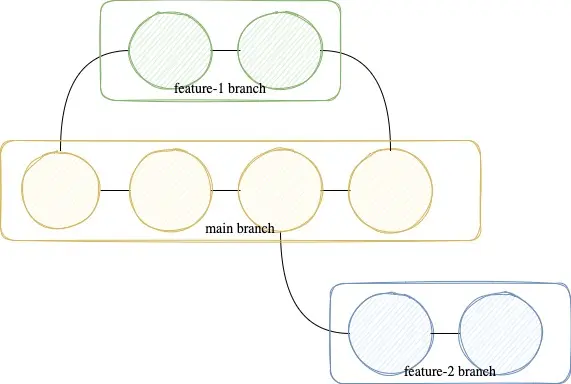

That leads us to the next candidate: What is a branch?. We literally branch of this linear structure into two or more lanes.

We can see we can "branch off" from a given commit and can also merge again into if we want later. That said one commit can have multiple descendants. If it has, we branched off at this commit. That is how we can find out what a common subset between two branches is. Just follow the trail of both until we see the same commit as parent in both branches.

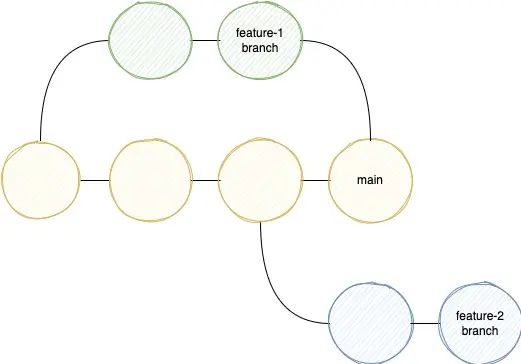

Now to be technically super correct: A branch is NOT the whole chain, a branch is just a label you give a commit. So the technical correct version looks like this:

So a branch is nothing more than a label to a specific commit(-hash).

Let's bring everything together before we continue:

We have a remote repository. A repository can be simplified as a bunch of branches, which consists out of multiple commits. origin is our local mirror of remote. On top we have a current working set of files where we work on. Every time we do git add followed by git commit we create a commit locally (not on remote, not on origin).

git push

As said before everything is local at the moment. git push pushes those changes to the remote repository. With that it automatically updates your *origin, as the origin should be the mirror of the remote. If you created a new branch which doesn't exist on the remote, git push will fail with the following error:

fatal: The current branch has no upstream branch. To push the current branch and set the remote as upstream, use

git push --set-upstream origin

Here we see everything in action we learnt so far. Git tells us: "Hey your branch does not exist on remote." And we are responsible for doing that. And that is what --set-upstream origin is doing for us. Now you could ask, why doesn't it do that automatically for us? And there are two reasons: 1. git tries not really to assume here anything. 2. You can have multiple "origins". But that I will cover later on.

Anyway the whole mechanism pushes your changes from bottom to top.

merge

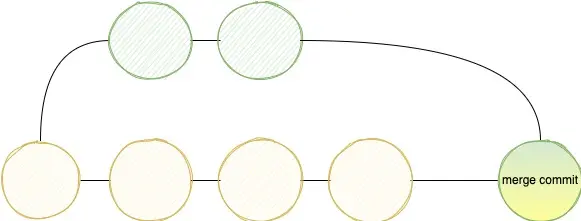

Just imagine you have two lanes which merge together to one. That is exactly what a git merge does, but instead of roads you have branches. The goal is to integrate changes from one branch into another. As we have two branches, one question: Which changes? And here is the neat thing, as I showed earlier we can go back both branches until we see common ancestor. From that point onwards we need the diff of our branch and want to integrate that into the other branch. What git does here is to create a new commit, which has two parents: One parent for each branch the commit came from. If we want to visualize that:

Of course it can happen that both branches can diverge a lot. This happens especially if you have long living branches. Well, don't have long living branches. Anyway we can have so called merge conflicts. This can happen if you have a function, which was changed on the main branch and on your branch. Now you have to entangle that mess. If you have done that, you will create a new commit.

The advantage of a merge is that we keep the original history intact. The timeline when a commit is done is before and after the merge the same. Another advantage is that if you encounter merge conflicts you only have to resolve them once. On the downside you have to resolve them all at once and not per commit. Another disadvantage is, that your history is not linear. This is important if you use git blame or more advanved features like git bisect, which of course I also have an article here.

git pull

Now that we know how merge works we can finally checkout what git pull really does:

# First we get the latest changes

git fetch

# Now we merge

git merge origin/main

We see a pull is nothing more than getting the latest and greatest state from origin via git fetch and then integrate those changes in your very local main branch (or whatever branch you have checked out at the moment).

rebase

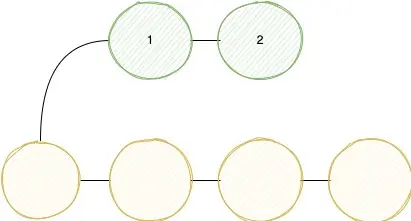

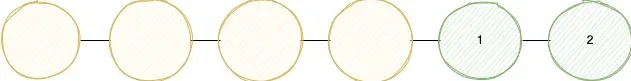

rebase is different than merge. The target is the same: We want to integrate changes from one branch to another. Rebase works like that: If we have a feature branch with let's say 3 commits and we want to integrate the latest main on it. Then we take every single commit from our feature branch and put them on top of the main branch one by one. That also means that we create new commits. Let's visualize that:

Step 1: We want to rebase the green branch onto the yellow one.

Step 2: We rebase the first commit onto the main yellow branch.

Step 3: And the second commit.

Rebase also allows you to modify the commit message, squash commits or drop them completely. If you are interested, have a look at the git blog. A word of warning: You rewrite the history of your branch. That is very dangerous and can have dangerous implications. I will not go into greater detail but will link here to the Atlassian blog as the topic deserves its own article.

You can also configure git to rebase changes when you pull. So if you use git pull --rebase it does the following:

git fetch

git rebase origin/main

You can also use rebase to "move" your branch onto a different base. I covered that in greated detail in my blog post: How to rebase onto a different branch.

HEAD

Often times you see HEAD. What is that special word? Well HEAD is kind of a special branch. The git website points it out really good:

The HEAD in Git is the pointer to the current branch reference, which is in turn a pointer to the last commit you made or the last commit that was checked out into your working directory. That also means it will be the parent of the next commit you do. It's generally simplest to think of it as HEAD is the snapshot of your last commit.

If you switch your branch, you switch HEAD as well. You can leverage HEAD in a lot of scenarios. For example let's say you want to rebase the last 2 commits, you can do: git rebase -I HEAD~2. Or earlier we saw how to push a new branch to the remote, you can simplify this by: git push -u HEAD. -u is the short form for --set-upstream.

origin/main vs origin main

From time to time you will see command which use the notation of origin/main and some which use origin main. To explain what is the difference we will see how exactly git pull is done. Earlier we saw it is fetching and merging. So let's see the commands in action to see exactly what happens. By the way git pull normally has 2 parameters: git pull <branch_name>. If you omit the branch_name git automatically fills in your current branch (aka HEAD). So whatI show you git pull is more git pull main. You can substitute main with any branch you are working on.

- We fetch the latest version of

mainfrom the remote. Rememberoriginis our local copy of the remote

git fetch origin main

2.We merge those changes into our branch

# Also merge has 2 parameters. The source and the destination

# If we omit destination it automatically takes the current checked out branch

# The long version of the command below would be: git merge origin/main main

git merge origin/main

That said origin/main is our local tracking branch for the remote repository. It represents the entity main on the remote, which we called origin. You can merge it, you can push it.

origin main is two things: origin and main. This is not a branch. With that you tell git to do something with main on origin. For example fetching or pushing changes.

To put it very simple in one picture:

Multiple upstreams

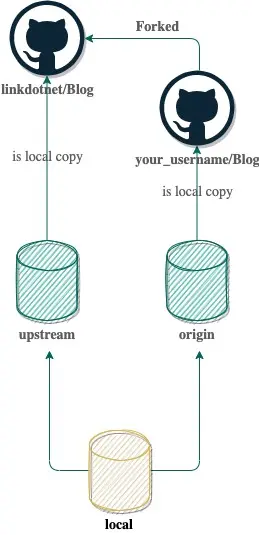

Earlier we saw that we can have multiple upstreams and you might ask why. A simple explanation is you forked a repository on GitHub.

If you fork a repository you made the whole situation a bit more complex 😄. Not only do you have to sync your local branch with the remote one, but you now also have to change your fork with the original one. And that is why we have multiple upstreams. Let's say origin is your version and upstream is the "original* repository you forked from. You can do a lot of stuff like:

# The original repo you forked from

git remote add upstream https://github.com/whoever/whatever.git

# Get the latest and greatest state from the original repo

git fetch upstream

# Switch to our main branch

git switch main

# Make the local copy the same as upstream. Hint: You can also use rebase

git merge upstream/main

# Push the changes to OUR remote

git push origin

Conclusion

I hope I could give a better understanding how git works internally. With that I hope some of the operations make more sense to you.